Real Cause of Decline of Muslim Culture; Suspension of Hikmah: A Tentative Analysis

Anwar Moazzam

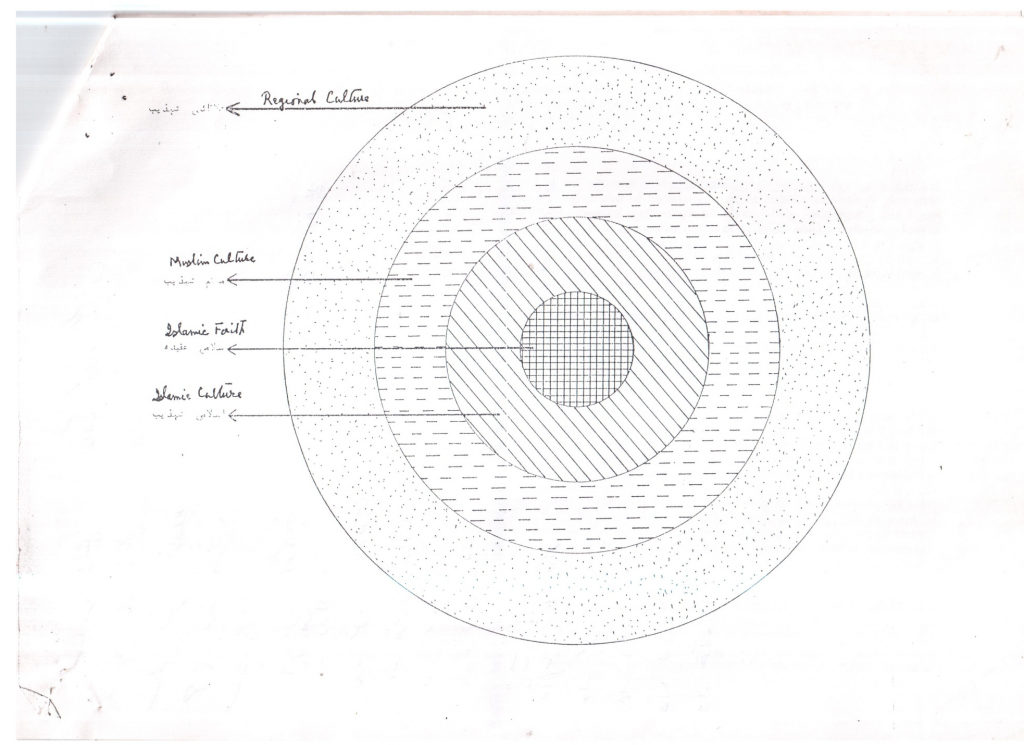

The strength and weakness of a culture depends, largely, upon the objective realities of time and space, on the one hand, and the ideas working upon those realities, on the other. A culture is strong if it is capable of maintaining its social, economic and political structure in a given area at a particular time with built-in ideological contents to keep pace with change. Social, economic and political structures are shaped by ideas – scientific, philosophical or religious. Ideas, on the other hand, are often, but not always, the outcome of the objective material realities, but they have to transcend the existing realities anticipating the future situation demanded by change.

Religion is one of the sets of ideas which shape culture. Religion is distinguished from other sets of ideas because of its claim that its ideas (beliefs) are eternal and not vulnerable to change. The question is how the unchanging ideas can keep pace with change. It appears illogical. How about other systems? Is it possible for any value-system to servive and produce results without unchanging, consistent principles and concepts? No. Absolutely true principles are essential to constitute a system of thought. So, religious and non-religious systems both are based on unchanging ideas. But the two differ on a very vital point. It is the question of authority on which these two systems are based. While religion places its beliefs on Divine authority and, therefore, rules out any possibility of their being invalid, the non- religious systems recognize the infallibility of their concepts until and unless they are proved wrong on the basis of human reason. Another distinction between the two systems is the recognition it non-material existence by religion and its rejection by non-religious systems. Now, religion claims that its beliefs are eternal because of their Divine origin and encompass all the possibilities of change in human terms, is too insignificant to affect the infinite validity of beliefs. Therefore, eternal beliefs can absorb the change. Rationalism of non-religious systems rejects all authority except that of reason and of the concepts based on reason.

The case of the rationalists is simple and straight forward. However, religion complicates its position by according a place to reason, as well, in its belief-system which is, to be sure, subordinate to divine authority and restricted to the physical world only. In Islam, this dual authority is represented in the Qur]an’s terms of Kitaab and Hikmah. While Kitaab, the Divine Will as reflected in the Qur]an, is the source of divine authority, Hikmah represents its operational wisdom in terms of human knowledge.

“God hath caused the Book and the wisdom (hikma): and what thou knowest not He hath caused thee to know, and the grace of God toward thee hath been great.”(4:113)

The Qur]an defines reason in its own way and assigns it a role which demolishes the frontier between the rational and the non-rational. This Qur]anic Reason (Hikmah) extends itself beyond the time-space and brings God-man relations into its area of operation:

“Read: In the name of your Lord who created: Created man from clot of congealed blood.

Read: Your Lord is the most bountiful one, who taught by the pen, taught man what he did not know.” (96:1-5)

Thus speaks Allah in His first address to Muhammad 610 years after Christ, assigning him the status of Messenger of Allah and the task of re-establishment of the eternal life system – Islam. Through Pen (qalam) and knowledge ([ilm), the creator man makes men aware of the Being and the beings. It was not a new message; it was the same eternal faith in one God and aakhirah earlier conveyed through His messengers in all regions of earth and through Abraham, Moses and Christ; but, now, it was in the version of ‘knowledge’ (‘ilm). Another reference to this dimension is available in the event of Adam’s designation as Allah’s vicegerent on earth.

“And when the Lord said unto the angels: Lo, I am about to place a vicegerent on the earth, they said: Will thou place therein one who will do mischief and shed blood, while we, we hymn Thy praise and extol thy holiness? He said: surely, I know that which ye know not. And He taught Adam all the names: Then showed the objects to the angels saying: Inform me of the names of these, if ye are in the right. They said: Glorious art Thou: we have no knowledge saving that which Thou has taught us. Surely, Thou alone art the knower, the wise: He said: Adam: Inform them of their names and when he had informed them of their names, He said: Did I not tell you that I know the secrets of the heavens and the earth?” (2:30-33)

Man, according to the Qur]an, was endowed with the knowledge of the names (asma) of all objects (kulluha). What is name (ism)? Name is the identification of the nature of the object. That is, the Qur]an’s justification for man’s creation in time and space, in spite of his mischievous nature, in his ‘knowledge’ of things besides God.

That Islam, that is, Qur]an, is knowledge is further explained by its view of man as the seeker of knowledge through his senses, intellect and intuition. The Qur]an invites people to know the Truth and does not impose it upon them. As Iqbal says, “The main purpose of the Qur]an is to awaken in man the higher consciousness of his manifold relations with God and the universe.”1 The repeated emphasis in the Qur]an upon ‘knowing’ the Truth indicates the importance which is attached to human faculty of reasoning. The ideal Muslims have been described variously according to the roles they play in society as Saaliheen, (those who follow the right Path), Muhsineen,(those who do good deeds in a manner calculated to stimulate the thought of good deeds in others and help them to rectify their errors and do else and practice equity, and not merely give freedom of action to those whowidh to do good deeds, but also help them in so doing), Mufliheen (those who reform or improve the condition of society).Siddiqeen, (those who meticulously adhere to fact and truth), Muslimeen, (those who confirm their will to the Will of God or submit) etc. – roles which cannot be done justice to without proper knowledge.2 Knowledge sometimes assumes the status of the primary quality of a Muslim. “Say: Shall they who have knowledge and they who have it not, be treated alike! (39:9) Meaningfullness of a thing or an event has been used by the Qur]an as an argument for truth.

“And many are the signs in the Heaven and on the Earth; and in the succession of the night and of the day are signs for men of understanding,

Who standing and sitting, and reclining, bear God in mind, and muse on the creation of the Heaven and of the Earth, O “Our Lord! Say they, ‘Thou hast not created all this in vain.’” (3:190-191)

Besides the external signs in the aafaaq (universe), “There are signs in your own soul.” (51:21) In another place the Qur]an says: “We have not created the heavens and the earth and whatsoever is between them in sport. We have not created them except to bear truth; but most people know it not.” (44:38-39)

As Dr. Syed Abdul Latif points out, “Wherever attention is drawn to the manifestation of life calling for reflection and introspection, expressions such as ‘herein are portents,” “herein are signs for folk who reflect”, for “men of knowledge”, for “folk who heed’, for “folk who understand”, echo and reverberate only to emphasize the importance which the Qur]an attaches to reflection as a means of obtaining insight.”3 Besides reason, another source of knowledge, according to the Qur]an, is history. “Certainly in their histories is an example for men of understanding.” (12:111) Inference through historical events is another form of rational understanding.

The Messenger said: “Acquire knowledge. It enableth the possessor to distinguish right from wrong. It lights the way to heaven; it is our companion when friendless, it guides us to happiness; it sustains us in adversity; it is a weapon against enemies and an ornament among friends. By virtue of it, Allah exalteth communities, and maketh them guides in good pursuits, and giveth them leadership; so much so that their footsteps are followed, their deeds are imitated, and their opinions are accepted and held in respect.4 Faith has been almost equated with knowledge. The religion of man is his sense of understanding, and he who has no sense of understanding, has no religion.5 The fourth Caliph, Ali, says: ‘knowledge is your lost property, get it from wherever it is available even from the associaters (mushrikeen,that is those who associate some one else with One God).6 Again, he says, “learn knowledge and when you have learnt it, bear its burden.”7

II

The above section was devoted to an attempt to explain the expression Hikmah–Qur]an’s Reason. Following are its implications:

-

Qur]anic Reason is based on Kitaab: the eternal principles, concepts, beliefs given by the Qur]an as explained and implemented by the Messenger, and as contained in ahaadith that are in harmony with the Qur]an

-

It covers both the inner and the external worlds (anfus and aafaaq)

-

It stands for sensory perception, reasoning and intuition.

-

Its object is to attain knowledge of the ultimate as well as of the concrete realities— Ultimate Reality, that is, God and akhira, concrete reality, that is, of nature, man and society

-

This two-fold knowledge implies its implementation through action ([amal) by man in time and space. While with the knowledge of the Ultimate Reality man achieves his own knowledge leading to a correct moral,social behavior, the knowledge of the concrete reality paves the way for the conquest (taskheer) of nature (through science).

Now, my submission is that Muslim culture remained strong as long as it was permeated by the Qur]anic Reason (hikmah) and weakened when it was ignored by the Muslims. So far as the Muslim culture is concerned this will be the case in future, also.

The Qur]anic Reason produced a culture based on knowledge – new knowledge of human mind and soul, of social, economic, political and ethical values and relations. This culture, which started taking shape during the later Umayyad period and reached its zenith during the second and third centuries of Islam, sustained its strength till the 6th Century. After that it lost its vigor and vitality except in mystic and theological thought.

The first six centuries of Muslim history witnessed the emergence of a dynamic culture with minds of exceptionally high order with a vast sweep covering hadeeth, tafseer, fiqh, philosophy, all natural sciences, medicine, and mathematics. Their achievements in philosophy and natural sciences did not consist of mere reproduction of Hellenistic sciences but a creative development of the same which, as is well-known, after being learnt by Europe, paved the way for the Renaissance. How to explain this phenomenon taking place in a culture without any scientific traditions of its own? The only plausible explanation appears to be in terms of the nature of Muslim culture throbbing with Qur]anic Reason. That is why other contemporary cultures could not achieve what the Muslim culture achieved.

Approaches oriented to theological aspects often tend to obscure the multi-dimensional thrust of Muslim culture during this period in various branches of sciences. Intellectual activity, naturally, started with the collections of traditions and jurisprudence along with initial discussion on the subject of freedom and predestination. It is to be noted that Abu Hanifah, the jurist, and Waasil b. [Ata, to whom is traced the beginning of the rationalist school,the Mu[tazilah, were contemporaries. The second century was dominated by Traditionalists (muhadditheen) and jurists (fuqaha) like Maalik b. Anas, Abu Hanifah, Shaafi[i and Ja[far al-Saadiq and mystics like Hasan al-Basri, Ibraheem b. Adham and Shaqeeq al-Balkhi. However, the most important development was opening the gates of Greek knowledge through translations under the knowledge-loving Abbasid Caliph, al Maamun. During this period,the esoteric aspect of the revelation was also added to its external aspect by the Baatiniyah. The third century was the most crucial insofar as it laid the foundations of a vast intellectual structure producing the six authentic collections of ahaadeeth, besides the Musnad of Ahmad b. Hanbal, Mu[tazilites, like [Azzaam, Jaahiz, Abu]l Hudhayl Allaaf, and Jubail; philosophers like Kindi and Faaraabi, the school of Zaahiriyah, mathematicians, physicists and astronomers like al-Khwaarizmi, alchemists like al-Raazi, historians like Ibn Hisham, Ibn Sa[d, al-Balaadhuri, Ibn Qutaybah and al-Tabari, in medicine, medical scientists like the Nestorian, Hunayn b. Ishaaq, geographers like Asma‘i Basri and Sarakhsi, etc. Side by side this legal, philosophical and social science contributors, seekers of truth like Dhu]l-Noon al-Misri, Baayazid Bistaami, Junayd al-Baghdaadi and Mansur al-Hallaaj were enriching the mystic thought of Islam.

Doors of human mind were wide open to all knowledge. One is specially struck by the spirit of free inquiry which ruled the scene. Till this stage no theological censorship existed although so far as the theological issues were concerned there were mutual allegations of deviations from the revealed truth among various schools and sects. However, secular sciences remained out of theological scrutiny. Within theology itself, as we shall see later, freedom of inquiry became suspect when it was directed towards the beliefs. Otherwise, hadeeth and fiqh, disciplines under the direct authority of revelation, were subjected to scientific and rational examination. In the sphere of hadeeth, the science of hadeeth criticism is based on several rational principles of riwaayah (narration) and diraayah (a discipline for ascertaining the authenticity of ahaadeeth.) In the legal field, the scientific spirit of the period was perhaps most forcefully expressed. The fact that there emerged several legal schools based on difference in the choice of sources of law and methods and principles of legal deductions (like, raa]y, qiyaas, istihsaan and ijma[) again indicates the freedom of intellectual decision making.

In the process of organization of theology certain polarization of authority took place. This authority having its validity in the Qur]an, the Hadeeth, the tradition of the companions of the Prophet and the interpretations by the later generation scholars, acquired a form of a frame reference to the orthodox school but, this authority was not as rigid and broad-based as it became later. The Qur]anic reason was there and made its presence felt in various impressions of culture.

The conflict between the given authority (manqul) and rational (ma[qul) came to prominence with the emergence of the Mu[tizilite Kalam during the third century itself.7 The Mu[tazilites, described as Qadarites by others and as ahl al-Tawheed wa]l-[Adl by themselves, are considered as the rationalists in the Muslim intellectual traditions. This does not appear to be totally correct if rationalism stands for acceptance of truth exclusively on rational grounds. The Mu[tazilah recognized the Qur]an as a revealed truth; what they aimed at is to prove the revelation in rational categories. This was quite different from the traditional view point of judging the truth on the basis of wahi. According to the traditionalists reason cannot remain independent of wahi and cannot subject the infinite to the finitude of reason. The Mu[tazilite [ilm al-kalaam developed around two concepts:

-

Absolute unity of God implying denial of attributes and

-

Justice of God implying that God’s justice necessitates that man must be the creator of his actions.8 The other related issues were the created nature of the Qur]an, denial of miracles (since it goes against causality), denial of beatific vision, etc. The Mu[tazilite objective of maintenance of absolute unity of God led them towards the denial of attributes as separate from His essence, while justification of reward and punishment under God’s justice required man’s being the author of his own actions. In their system, the Mu[tazilite employed logic and theoretical reason. Shahristaani sums up their position by putting all objects of knowledge under the authority of reason.9

One of the reasons underlying the emergences of [Ilm al-Kalaam 10 appears to be the induction of the Magians, the Jews and the Christians in the academic life of the early Abbasid caliphs who had allowed full freedom in religious affairs. These people with a firsthand knowledge of Islamic beliefs started raising awkward questions which could not be answered through the traditional methods and created doubts in the beliefs of the Muslims. Caliph al-Mansur and al-Mahdi desired that these objections should be satisfactorily refuted. Almost during the same epoch a deep acquaintance with Greek logic helped the Muslim defenders of faith to meet this challenge on more solid grounds. This step, Shibli Nu[maani points out, was similar to the steps of the Muslim scholars, earlier, to meet the needs created by circumstances in tafseer, fiqh, Arabic lexicography and grammar, etc.11 Notwithstanding the bitter resentment of the traditionalists against rationalization of Islamic beliefs by the Mu[tazilites,it remains a fact that the latter always reained rooted in the Islamic belief system in their own way.12

On the other hand, logic and reasoning, for the first time, found a place as an instrument of knowledge in scholarly pursuits. Its most forceful expression was made in the system which emerged during the 4th century—Asha[rism, as a refutation of the Mu[tazilah. Al-Ash[ari (d. 345/956), a well versed in the Mu[tazilite methods and a Mu[tazilite himself in his early years, developed a formidable scholastic system treating wahi as the primary authority, which has acquired an almost permanent place, at least in the Sunni theology.

Al–Ash[ari could totally agree neither with the Mu[tazilite method of dialectical reasoning nor the uncritical traditional school. He attempted at reconciling the manqul (what has come from generation to generation) and the ma[qul.( dedductio by reasoning) Applying logical reasoning in the Mu[tazilite fashion, he refuted their interpretations of concepts of God’s justice, beatific vision, causality, etc. Ash[ari’s main objective was to re-assert, in philosophical terms, the abstract as well as the imminent nature of God as against the Mua[tazilite God which could neither be known nor felt. Hence his view that God is the creator of every action and of both cause and effect (later emphasized by al-Ghazali). The chief point of contention between the Mu[tazilah and the Ashaa[irah appears to be whether God has become alienated with his creation after the act of creation or He is still in active relationship with man and the nature. Earlier the muhaddithun (traditionalists) held that such doctrines were to be believed, without asking why (bilaa kaif). The Mu[tazilah and the Ashaa[irah, both, posed the same question since the answer to this question was vital in he Rationalization of Islamic beliefs had produced an equally opposite view-point taking the revelation in literal meanings leading to anthropomorphic representations. Asha[ri avoided both these positions. Through the doctrine of mukhalafa (difference in meaning of attributes of God as they are and as they are understood by man), that is, attributes of God like seeing, hearing, knowing, cannot be understood in terms of human understanding), the Ash[arites made a distinction beween the reality and its understanding. They contended htat the meaning(mafhum) of God’s essence and attributes are not one but their reality (haqiqah) is one.13 On the issue of human freedom of action Asha‘ri almost agrees with the fatalistic school although he believes in kasb, that is, human freedom in axcquiring an action by God’s will. Al-Maaturidi, a contemporary of al-Ash[ari, deserves more attention as one who attempted to adopt a middle course, like al-Ash[ari, between the Mu[tazilah and the Traditionalist.14 Although he agrees on several points with the Mu[tazilite rational interpretations, he restricts the role of reason within limits and not in matters of religion where only revelation is the final authority.

Ash[arism, however, obtained its fullest exposition in al-Ghazali (d. 1111 A.D.), in spite of his disagreement with the former on several issue. In between al-Ash[ari and al-Ghazali, the philosophers had entered the scene in a big way. Al-Kindi (d. 260/873), al-Farabi (d. 339/950) and Ibn Sina (d. 428-1037), great minds mastering all sciences besides philosophy, steeped in Platonic and Aristotelian traditions, further consolidated rationalization of Islamic doctrines. Apart from their individual thoughts on various controversial issues, we have to note that all the three philosophers, like the Mu[tazilites, did not question the philosophical validity of essential Qur]anic doctrines; they argued that philosophy and religion are not mutually exclusive but are co-terminus on the truth. They held revelation as a direct experience of truth by the Messengers of God and rationally valid. As a whole, rational validity is what they are concerned about. Ibn Sina is perhaps the first philosopher who believed in the Qur]anic expression of truth symbolically and not literally and suggested that the common minds should follow the literal meaning.

Al-Ghazali’s problem was quite different from his predecessor. He was working in a society which, unlike the previous epoch, was passing through great social and political strains. The state was crumbling under the divisive undercurrents. The Turks were gaining the power. The culture was fast losing its power obtained from the Qur]anic Reason. The common masses that up till now, because of political-economic stability, were considered to be secure from the Islamic or non-Islamic thought currents on the higher intellectual levels, appeared vulnerable to all non-traditional views. That ordinary minds acquired greater importance during the 9th century is indicated in the methodology of al-Ghazali itself. What Ibn Sina had suggested earlier regarding the advisability of literal understanding of Qur]an, was developed by al-Ghazali in to a deliberate division of knowledge on two levels – one for the learned and the other for the layman.15 Explaining the aim of kalam as prevention of bida[ and removal of doubts, he said that he had written this science in two ways—firstly, for the common people to safeguard their beliefs and in such works (which include Ihya]) the real facts had not been mentioned and, secondly, the works, which discuss those facts (like Jawahar al-Qur]an). The latter works, he suggested were to be studied only by men of learning and of pure conduct who had no other interest except of knowing the truth. The delicate doctrines demanding such care included essence and attributes of God, human actions, Day of Judgment, etc. (such division of knowledge was latter suggested by al-Raazi, as well as Ibn Rushd).16

Al-Ghazali after passing through various ‘stages of deliverance from error’ reached to the conclusion, that true knowledge could be achieved only by direct religious experience; all other knowledge was false. With intuition as the only source of ultimate truth, al-Ghazali went on to demolish philosophy in his Tahaafut al-Falaasifa. In fact the discussion on the manqul and the ma[qul reached a decisive stage in al-Ghazali’s Tahaafut and its refutation a hundred years later by Ibn Rushd.

Al-Ghazali criticizes the philosophers on twenty points, seventeen metaphysical and three physical or on nature. He refutes the philosophers’ views that the world is uncreated, God is devoid of attributes, God’s ignorance of the particulars and that there is causality. Secondly, he challenges that the philosophers cannot prove God’s existence and essence and soul as a self-subsisting essence. Philosophers have to be atheists. It is to be noted that in the Tahaafut, al-Ghazali’s objective is only to expose the errors of the philosophers and not to expound his own views, and, in the process, to refute the Aristotelian philosophy as available in al-Farabi and Ibn Sina. Al-Ghazali accused the philosophers of heresy on three points which violate Islamic beliefs: (i) Eternity (qidam) of the world and of all essences, (ii) God does not possess the knowledge of the particulars and, (iii) Denial of bodily resurrection. On other points, he suspends his judgement.17 Restricting ourselves to his method, we select a few arguments denying causality. He says that causal relationship is based merely on the observation of a necessary relationship between two incidents in immediate succession, viz., fire burning cotton. The philosophers believe that fire is the cause of burning of cotton. That is, fire acts by its nature and not by acquisition (kasb). Al-Ghazali rejects this explanation and argues that the creator (faa[il) of burning and of the quality of being burned in cotton is God. What is the proof that fire is the creator of burning except observation? Al-Ghazali, however, concludes that causal relationship does exist, but it is because of the will of God. With the same basis of the God’s will, al-Ghazali goes on to prove the occurrence of miracles. If it is recognized that matter can change its form from one kind into the other in a period of time, then God can reduce this time-span and a rod can become a snake in no time.18

About one hundred years later, Ibn Rush wrote a refutation of the Tahaafut. Ibn Rushd held that the Qur]an permits philosophical investigation for the knowledge of God and the universe. “True knowledge is the knowledge of God, of all other things as such and of the happiness and unhappiness in the hereafter”19 Regarding a possible conflict between the manqul and the ma[qul, Ibn Rushd suggests that in such a case the manqul is to be so interpreted (that is) by ta]weel that it conforms with manqul.20 Like al-Ghazali, Ibn Rushd also is of the view that the inner meanings of the Qur]an are not to be disclosed to the common peope.19 He rejects al-Ghazali’s assertion that mystic experience is the only source of knowledge of God since this view goes against the Qur]anic insistence on speculation. Regarding al-Ghazali’s charges against the views of the philosophers, Ibn Rush accuses him of not having studied them, particularly Aristotle in original sources but only in al-Farabi and Ibn Sina who did not represent him faithfully. He alleges al-Ghazali of ascribing views to those Greek philosophers which they did not actually hold. Al-Ghazali’s target, he points out, were in fact all those philosophical views which were floated by various sects among the Muslims in his time including the Baatiniyah, and, in that way al-Ghazali’s criticism was valid. He draws attention to the fact that beliefs like miracles, beatific vision or bodily resurrection had no connection with Greek philosophy, neither were they discussed by those philosophers. Again, Ibn Rushd makes a distinction between matters of Shari[ah and those of philosophy. Matters of Shari[ah cannot be discussed; however, matters about which Shari[ah is silent can be discussed.21

On al-Ghazali’s denial of causality, Ibn Rushd says that it was done in order to prove the occurrence of miracles. Ibn Rushd holds that the only miracle is the Qur]an which does not signify kharq [ada (against nature, abnormal)but it can be established by perception. Then he argues that things are perceived by the intellect along with their causes. He who denies causes, denies the intellect. Denial of causes, therefore, implies denial of knowledge.22 According to him al-Ghazali’s denial of causes is mere sophistry. While leveling charges against al-Ghazali, Ibn Rushd does not treat al-Ghazali’s views as truly representative of him. According to him, al-Ghazali was apprehensive of his reputation among the orthodox of being a follower of the philosophers himself and the Tahafut was written to counyter this opinion.23

The above reference to this controversy was made in order to indicate the state of nature of the thought currents during the 5th century Hijrah when al-Ghazali attacked philosophers. The attack was decisive in discrediting philosophy in the later Muslim tradition to such an extent that Ibn Rushd’s counter refutation could not salvage the situations. Al-Ghazali’s main objection was against the rationalization of those doctrines which, in his opinion, could lose their religious validity when rationalized. Otherwise, he had no objections against philosophy or rationalism in matters other than metaphysical. He gave currency to logic and himself used philosophical methods in his works to the great resentment of the orthodoxy. It helped in encouraging the teaching of ma[qulaat (rational sciences) in the educational centres, although not for the progress of these sciences but for their refutation. This paved the way for the emergence of leading figures like Shaykh al-Ishraaq, Shihabuddin Suhrawardi Maqtul and al-Razi, who were the masters of both rationalist and traditional sciences.24

The foregoing account offers two conclusions:

(i) Scholastic and philosophic traditions up to al-Ghazali were focused mostly on the methodology of investigating the relationship between wahi and reason, and (ii) both had gradually become irrelevant to the actual problems of society and culture. The net outcome was that the scope of Qur]an’s Reason was restricted to metaphysics and the culture of knowledge lost its vigor. Earlier, all discussions were directly or indirectly related to concrete problems of man and culture.

Al-Ghazali, as a mystic-philosopher, although intended to demolish philosophers’ hold but in the process helped in removing philosophy from the intellectual scene. His anti-rational approach appears to be one of the chief causes of the Muslim cultural decline which set in after him. The other reasons being the destructive impact of the Mongol invasion, passing over of the state from the Arab-Persians into the hands of the Turks who had no cultural tradition of their own and, thirdly, absence of the participation of the ruling elite, in general, in the academic life. Closure of the door of ijtihaad, declared by the theologians, was a decisive negative factor, freezing the capacity of Muslim culture to keep pace with change. In the post Ghazalian period the intellectual activity shifted from the east to Spain in the West which witnessed the emergence of Ibn Baja, Ibn Rush and Ibn Tufayl in philosophy and Ibn [Arabi in mystic thought. In fact the later centuries can boast only of mystic thinkers like Rumi, Shihabuddin Maqtul, al-Jili, Shakh Ahmad Sirhindi, Sadr al-Din Shirazi – all from central Asia.

However during this period there was one thinker, Ibn Khaldun, who tried to re-establish the link between thought and culture. Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406) sounds very modern in his objective of development of a science of culture ([umraan) which should be demonstrative, devoid of dialectical, rhetorical and poetic arguments. He accepts the validity of divine law but rejects philosophers’ attempts at rationalizing it. Ibn Khaldun gives due importance to philosophy and science in their own spheres, but criticizes philosopher’s role as a theologian.25 He holds that kalaam is not necessary for faith, but is required for the defense of faith. Likewise, it is futile to reconcile religion with philosophy; it is unscientific to do so. Therefore, Ibn Khaldun suggests for a study of culture on the basis of natural sciences with a focus on the social solidarity ([asabiyah) and concrete needs of society. In this study faith remains as one constituent factor in its simplest form. Needless to point out, this approach was never incorporated into the Muslim tradition mainly because the post-Ghazalian age had become unfamiliar with any sources other than the manqul.

The following appears to be the factors underlying the decline of Muslim culture:

-

Primary place was given, instead of hikmah, the Qur]anic Reason, to the traditional manqul theological methods for understanding Islam

-

Instead of Kitab and Hikmah, multiple authorities taking a partial view of the Qur]anic Reason came to dominate the intellectual scene.

-

Closure of the gate of ijtihaad for fear of disintegration of a unified Shari[a.

-

Transformation of culture of knowledge into a culture of theological censorship.

For a rethinking of this whole problem, the Muslim world had to wait till the middle of the 19th century when Muslim culture had to come face to face with the powerful scientific brilliance of the West with its political and economic advances into Muslim lands. Discussions on mutual relationships between Islam and science which were started in 19th century have still not reached any decisive stage. Modern [Ilm al-Kalaam, the development of which was suggested by Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan and Shibli Numani in India is still to be developed. Sir Sayyid himself did not do more than restating mostly the Mu[tazilite positions in a different context. Shibli also could do the same according to the change temperament of the age.

The problem, as suggested by Ibn Khaldun, is not of proving the rational basis of Islamic metaphysics but of providing a functional ideological apparatus for Muslim culture. It is to be admitted that Qur]anic Reason has been blurred because of the theological and philosophical authorities standing between it and the contemporary cultures.

From the 5th century of Islam onward, certain distortions in the Qur’anic theory of knowledge have taken place. Firstly, reason has been relegated to the background and the whole area of knowledge is occupied by the post-Qur]an and post-Messenger authorities. Secondly, sciences have been divided into artificially mutually antagonistic categories of Islamic and non-Islamic sciences. Thirdly, the natural and social sciences could not develop as a result of the first and second distortions. Fourthly, instead of functioning as a system of life as a whole, Islam has been transformed into a mere theology, thus delinking it from culture itself. These distortions are to be removed, as early as it is possible. For this the Qur]anic Reason (hikma) is to be re-stated and re-asserted in its virgin form and not in its authoritative versions constructed in history. The crucial question is not the survival of Islam as a faith because it would always remain alive.. The question is of the survival of Muslim society with its political, social and economic institutions in the contemporary world.

References

-

Iqbal, Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam (Lahore, 1994), p. 8.

-

Dr. Syed Abdul Latif, The Mind Al Quran Builds, Delhi,1977 edoition,pp.30-31

-

Dr. Syed Abdul Latif, Bases of Islamic Culture (Hyderabad, 1959), pp. 88-89

-

Ibid., p. 96

-

Ibid.

-

Ibn Abdul Barr, Al-[Ilm Wa]-l[Ulama], Urdu tr., Abdur Razzaq Malihabadi (Delhi, 1953), p. 8.

-

Ibid., p 83.

-

Called Kalaam either because the most discussed issue had been the Kalaam of God or the word Kalaam stood for logic (mantiq). Shibli Nu’mani supports the latter opinion. [Ilm al-Kalaam, (Karachi, 1964), Vol. I, pp. 35-36

-

A. J. Wensinck, The Muslim Creed (Cambridge, 1932), pp. 62-63.

-

Shibli, op. cit., pp. 34-35

-

Ibid., p. 35.

-

Abdul Hudhayl Allaaf, a prominent Mu[tazilite, is reported to have converted three thousand persons to Islam through his discussions. Ibid., pp. 38-39.

-

M. M. Sharif, History of Muslim Philosophy (Germany, 1963), Vol. I, pp. 227-28. See also Al-Ash[ari, Maqalat al-Islamiyin, Urdu tr., Muhammad Hanif Nadvi, Musalmanon Ke Aqaid Wa Afkar, (Lahore, 1968), Vol. I.

-

Sharif, op. cit., pp. 259 et seq.

-

Shibli, op. cit., Vol. II, pp. 158-160.

-

Ibid., Shibli refers to such differences of opinion in Ghazali’s works.

-

Tahaafat al-Falaasifah, Urdu tr., Mir Valiuddin (Hyderabad, 1962), p. 289.

-

Ibid., pp. 219 et seq.

-

Sharif, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 544-45

-

Ibid., p. 546

-

Ibid., p. 557

-

Ibid., p. 559

-

Abdus Salam Nadvi, Hukama-i Islam (Azamgarh, 1953), Vol. I, pp. 423-29.

-

Ibid.,pp. 422-23

-

Sharif, op. cit., p. 972.